Play through the life story of a seventeenth-century Englishwoman.

Optionally, use the fortune telling methods to make key decisions.

About the exhibition

This digital exhibition was created by Dr Martha McGill and Dr Imogen Knox at the University of Warwick. Special thanks go to Francesca Farnell, who was involved in designing and running an earlier, in-person version of the exhibition. We are particularly grateful to Francesca for allowing us to use her logo design and recordings of candle wax dripping for this version of the exhibition.

An in-person exhibition was first planned for the 2021 British Academy Summer Showcase. In response to Covid-19 lockdowns, it became an online lecture. In 2022, physical exhibitions were hosted at Coventry Central Library and the University of Warwick as part of the Resonate Festival.

We are grateful for support and funding from the University of Warwick and the British Academy.

This exhibition explores methods of divining occult (or hidden) knowledge employed in England, Scotland and Wales between 1500 and 1750.

For the most part, we examine divinatory practices. It was common for early modern people to interpret unusual occurrences as divine forewarnings. There also abounded stories of visions or sounds imparting information about significant events; for example, there are numerous accounts of people seeing apparitions of dying loved ones (wraiths), seeing strange lights (such as corpse candles), or hearing shrieks before deaths. Some stories of omens do appear in the exhibition, for example in the sections on animals. There are also stories of involuntary visions; second sight especially straddled the boundary between being a divinatory practice and an unsought, uncontrollable gift (or curse). But we have not systematically discussed omens or premonitions that people did not seek out.

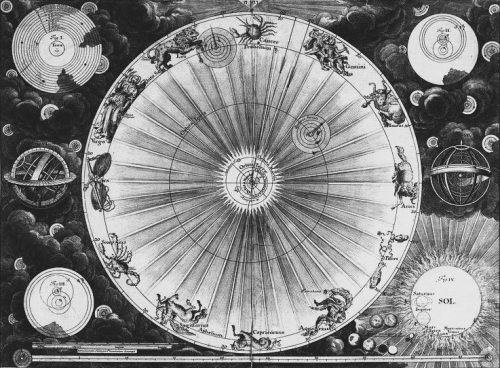

Some of these methods were much more commonly used than others. Astrology was an important and widespread practice, whereas pulling up kale was a relatively obscure folk custom that is not documented before the eighteenth century. The selection of practices covered here was guided in part by historical considerations, but also practical ones. Kale (really a subset of nature) and candle wax feature primarily because they are visually engaging and make for fun interactive activities.

Some practices examined here were primarily divinatory in nature; others, such as prayer, only rarely became so. As we have sought to explain, different divinatory methods were employed by different social groups, and might be underpinned by different explanatory models. There was significant difference between prophecy – whether understood as a ravishing religious experience or a scholarly practice of textual interpretation – and folkloric traditions about ominous birds. Conjuring spirits was a very different practice from observing the weather. The orthodox religious practice of prayer, the carefully codified and quasi-scientific study of astrology, and the popular custom of divining with a sieve and shears all have distinct histories. In bringing these practices together, we seek to show the wide range of early modern divinatory techniques, without meaning to imply that these techniques might be used interchangeably.

To improve accessibility for a non-specialist audience, we have modernised spelling and grammar in primary sources.

For the most part, we have provided inline citations for text only if we are quoting directly, or referencing particular primary sources. Secondary source material used for general information is cited on the Further Reading page.

Images are used under appropriate Creative Commons licenses, and are typically referenced in captions. An exception is the thumbnails on the home page, above. Most of these are details (sometimes edited to remove backgrounds) from images on the pertinent page, and are cited there. The following are exceptions: clients;1Image from Diviners page. the Bible and further reading;2Details from woodcut in Jost Amman, Charta Lusoria (Nuremberg, 1588), HAB Wolfenbüttel. bones;3Jan Luyken, Geraamte van een Paard (1680), after Cornelis van Dyk (1642-86), Rijks Museum. candle wax;4Detail from woodcut in John White, A Rich Cabinet, with Variety of Inventions (London, 1689), p. 36, Google Books. dreams;5Detail from woodcut in Deaths Dance (London, [1625?]), EBBA. elements;6Detail from woodcut in A Briefe Sonet Declaring the Lamentation of Beckles, a Market Towne in Suffolke (London, [1586-1597?]), EBBA. kale;7Detail from woodcut in Any Thing for a Quiet Life (London, [1620?]), EBBA. scrying;8Detail from woodcut on title page of Hic Mulier, Or, the Man-Woman (London, 1620), Google Books.; second sight.9Detail from woodcut in The Beggers Delight ([London], [1680?]), EBBA.

Martha McGill and Imogen Knox, ‘Stars, Sieves and Stories: An Interactive Exhibition about Early Modern Divination’, online exhibition (2024), https://starsandsieves.com, accessed [date].

We would love to hear your thoughts on the exhibition. Please use this form to let us know about things you liked, or things that could be improved.

You may also be interested in Witch Hunt 1649, a pair of free, educational card games about the Scottish witch hunts developed by Dr Martha McGill.

Engraving from 1732 showing Copernicus’s astronomical system, as well as those of Ptolemy and Tycho Brahe. Zodiac signs are also depicted.10Line engraving by J.A. Fridrich after J.M. Füssli, 1732. Wellcome Collection.