Early modern people had some understanding of the natural processes that led to unusual weather events, but religious explanations were also common throughout the period. Droughts, floods, earthquakes and even cloud formations might be seen as portentous. When several floods occurred across England in 1674, one author advised that readers ‘humble their souls under the hands of providence’ in order to ‘divert this threatening visitation of unseasonable weather’.1Sad News from the Countrey, or, A True and Full Relation of the Late Wonderful Floods in Divers Parts of England (London, 1674), title page.

In addition to using the weather to predict future events, early modern people also used divinatory methods to predict the weather. A great number of ‘almanacs’ were published in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, often employing astrological techniques to proffer weather forecasts for the forthcoming year and advise on the appropriate times for farming activities. Writing about the weather for 1572, Thomas Hill predicted ‘The first day [of March] fair and warm, with clouds in the afternoon, and some wind; the second, great wind or a tempest, with rain in the morning’.2Thomas Hill, A Prognostication Made for the Yeare of our Lorde God, 1572 (London, 1572), under March. Just as dramatic weather events were understood in both natural and supernatural terms, weather prediction could combine naturalistic techniques with occult methods.

Woodcut from 1568 of an astronomer at work.3J. Amman, woodcut of astronomer (1568), Wellcome Collection.

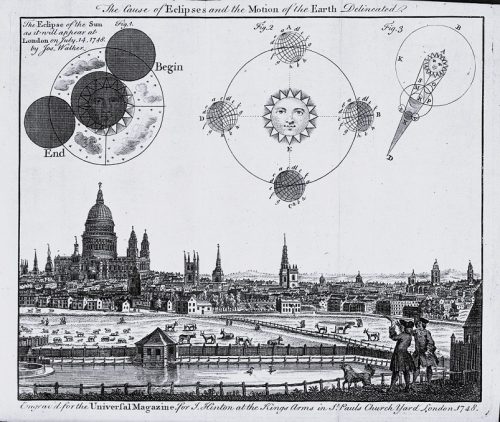

A 1748 engraving of an eclipse.4Wellcome Collection

‘Black Monday’, a solar eclipse that occurred on 29 March 1652, was said to predict the end of the monarchy. While this was not technically a weather event, the upheaval concerning it demonstrates the contemporary interest in monitoring and understanding the patterns of the skies. The extract below is from a poem mocking anxieties about the eclipse.5On Bugbear Black-Monday, March 29 ([London], 1652).

Why gaze ye brain-sick people on the sky?

To seek in Heaven some uncouth prodigy?

Is your religion from the Chaldee [Chaldeans] ta’ne?

Or traffic you divine things for profane?

What frantic prophet is amongst you sprung

To cheat your understanding with his tongue?

Or what magician has bewitched men

With unknown-characters of’s horrid pen?

And why (ye frighted Women!) do ye shake?

Must an eclipse needs make the Earth to quake?

The heavens their order, and due motion keep.

Why you disord’red? startle? sigh? and weep?6On Bugbear Black-Monday, March 29. 1652 ([London], [1652]).

This image and text are from a 1607 pamphlet about a series of dramatic floods in English counties. Can you bring some order to the scene of chaos?7A True Report of Certaine Wonderfull Overflowings of Waters (London, 1607), title page (woodcut) and p. 3, image via Wikimedia Commons.

Albeit that these swellings up and overflowings of waters proceed from natural causes, yet are they the very diseases and monstrous births of nature, sent into the world to terrify it, and to put it in mind, that the great God (who holdeth storms in the prison of the clouds at his pleasure, and can enlarge them to breed disorder on the Earth when he grows angry) can as well now drown all mankind as he did at the first; but that by these gentle warnings, he would rather have us come unto him, and fly from the points of more deadly arrows of vengeance, than utterly to perish.

Most almanacs were produced by men, but between 1658 and 1664 there appeared annual almanacs attributed to a woman called Sarah Jinner. Aimed at women, the alamancs drew on astrological theory to advise on medical and sexual problems. Jinner also offered prognostications based on the weather.8Sarah Ginnor, The Woman’s Almanack (London, 1659), under Monthly Observations.

If it be on New Year’s Day that the clouds in the morning be red, it shall be an angry year with much war and great tempests…

On Shrove Tuesday whosoever doth plant or sow, it shall remain always green … If you hear it thunder, that … betokeneth great wine and much fruit…

If on Palm Sunday be no fair weather, that betokeneth to goodness. If it do thunder that day, then it signifieth a merry year, and death of great men.

…take heed to the oak apples about Saint Michael’s day, for by them you shall know how that year shall be. If the apples of the oak trees when they be cut be within full of spiders, then followeth a naughty year. If the apples have within them flies, that betokens a meetly good year. If they have maggots in them, then followeth a good year. If there be nothing in them, then followeth great dearth. If the apples be many and early ripe, so shall it be an early winter, and very much snow shall be afore Christmas, and after that it shall be cold.

Cover of a 1787 almanac for women.9Wikimedia Commons.